- news

Wednesday, 10th September 2025

Access to justice for victims of crime with low proficiency in English: progress, challenges and lessons learned

In this blog post, LCN's Strategic Projects and Policy Officer, Laura Chilinţan, shares insights into improving support, accountability and trust for victims with language needs.

The first right that the Victims’ Code accords is “to be able to understand and to be understood,” but are public services geared to bear it out?

Last year, the Victims’ Code was written into law in the Victims and Prisoners Act 2024 but, since then, practical progress on it has stalled. Safeguarding minister, Jess Phillips MP, admits that victims’ trust in the criminal justice system has been “broken.” Baroness Newlove, the Victims Commissioner for England and Wales, has expressed concern that these challenges affect victims’ reporting behaviour.

LCN’s report into police standards and practice and our learning since its launch shows how this situation can be improved.

Background

Crime can have a profound impact on anyone, but for victims in the UK who speak limited English, the journey through the justice system is fraught with additional challenges. This issue is more widespread than it might seem. According to the last Census, 5.1 million UK residents speak English as an additional language, and over one million report not speaking it well or at all. A fifth of these individuals are UK citizens.

While the Victims’ Code mandates accessible information and support, many victims face a starkly different reality. For them, navigating police procedures, accessing support, and securing fair outcomes is often an uphill struggle—in particular when other vulnerabilities, such as insecure housing or labour exploitation, compound their circumstances. Commonly, it is not deliberate hostility that drives victims’ adverse experiences but institutional shortcomings, such as lack of resources or inadequate procedures.

Simona’s story

Simona (not her real name) is a Lithuanian woman who was evicted from her shared accommodation and subsequently arrested following an altercation. Initially, the police presumed she was the aggressor. However, through the intervention of Harrow Law Centre, it emerged that she had been subjected to repeated sexual assaults by a neighbour, and her previous attempts to report these incidents to the police had been disregarded. When she defended herself, the police initially misidentified her as the perpetrator rather than the victim. It was through the Law Centre’s involvement that Simona's account was fully understood, the police dropped charges, and she was offered appropriate support.

Farouk’s story

Farouk (not his real name), a Syrian Kurdish refugee staying in an Ipswich hotel, was assaulted by another resident. The police were initially notified through a community interpreter but decided not to pursue the case. Visiting Suffolk Law Centre, Farouk was helped to file a formal complaint, alleging race discrimination and police inaction. The complaint was upheld: an Inspector admitted investigative errors, apologised for the oversight, and reopened the case as racially aggravated assault. Statements were collected via an interpreter, and Farouk was provided with victim support. The perpetrator was later arrested.

Our report

These stories show the important role of legal advice organisations, such as Law Centres, in advocating for victims. However, after years of cuts to advice services, such vital support is in short supply across the country. It is all the more important, then, for police forces to get things right from the start.

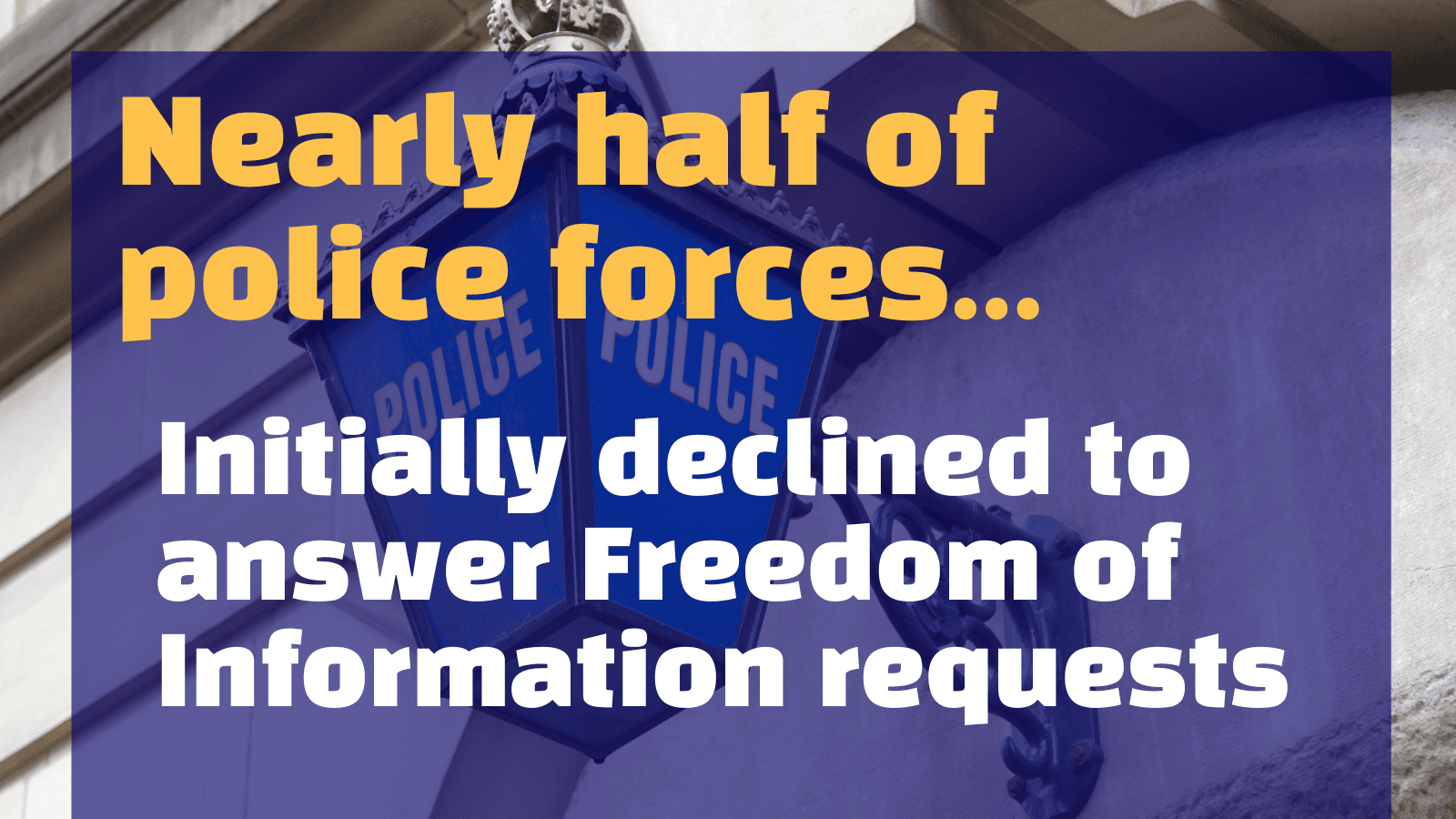

This intention drove a report published by the Law Centres Network in October 2024. It examines how police forces across England and Wales deal with victims of crime who have low proficiency in English. The report was the culmination of three years of research, preparation and analysis, drawing on Freedom of Information Act (FOI) requests sent to every police force in the country. Each force was asked about its policies and procedures, officer training and ongoing development, and language support provided to victims and complainants. Among its findings, the report highlighted that police responses to language needs are often inconsistent and insufficient.

Taking the report further

Following the report’s launch, we have used it as a basis for engaging with various professional stakeholders, such as the National Police Lead on Languages, the London Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC), and the London Victims’ Commissioner’s Office. Discussions have provided valuable insights into the day-to-day pressures police forces face when supporting people who speak English as an additional language.

We heard directly from practitioners about the complexities of recording language needs, and the realities of interpreter provision and availability. The conversations highlighted areas for further improvement. They also illuminated the critical role of consistent data collection, legal aid reforms and interpreter compensation in ensuring access to justice.

The value of a data-driven approach

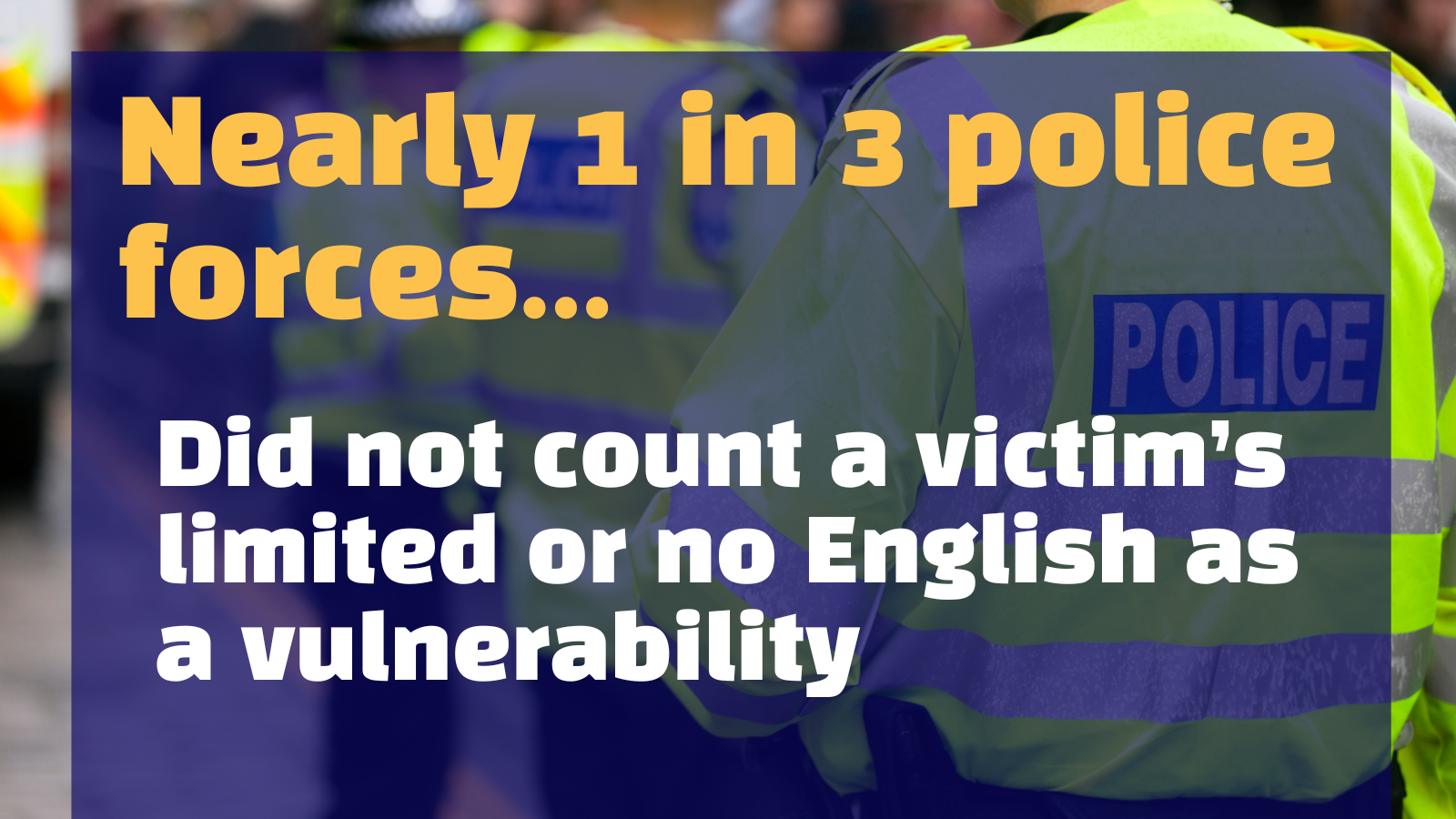

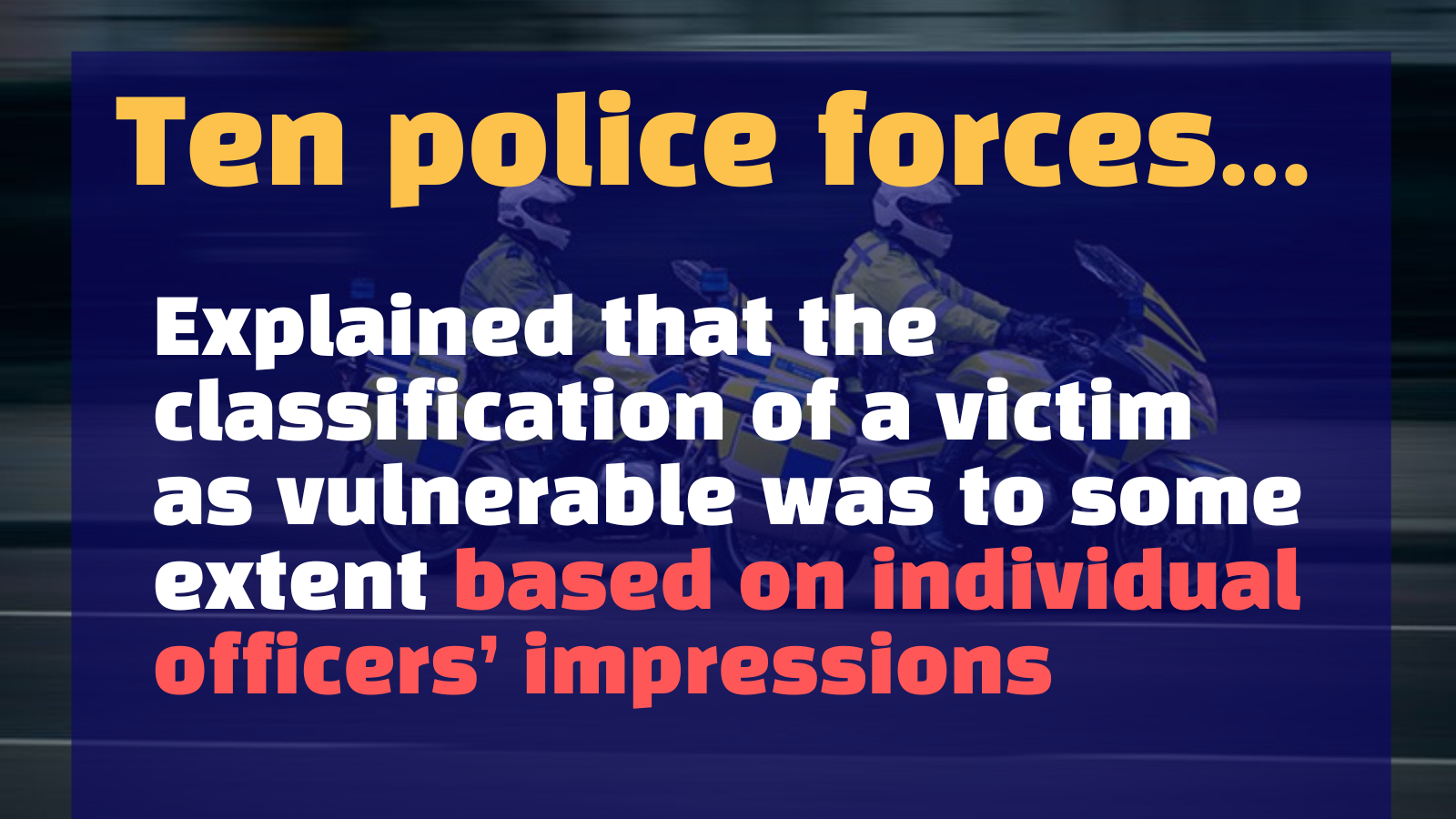

A recurring theme in both our report and subsequent engagement was the inconsistency in how police forces collect and record victims’ language needs. Some forces rely on individual officers’ discretion, risking under-identification of support needs at crucial moments. At the heart of overcoming this challenge is the systematic and consistent collection of data. We recommend establishing a national, standardised protocol for data collection on victims’ language proficiency, with regular publication or disclosure of the data. This will not only support more consistent practice but also facilitate benchmarking and performance improvement across UK police forces.

Fundamental to this effort is that every crime report should capture the victim’s language profile. Implementing this measure would ensure that police officers routinely consider whether victims comprehend proceedings, require interpretation services, or need information presented in an alternative format. Without such comprehensive data, there can be no accountability, no means of assessing progress, and no effective way to identify where support mechanisms are inadequate. Moreover, the routine recording of language needs would not only improve outcomes for victims but also inform training, enhance resource allocation, and ultimately promote fairness across the justice system.

Such improvements could be led by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC), which oversees policing progress and standards. Arriving at a common data framework would improve accountability on a local level by putting respective forces’ performance in broader context. It would also improve outcomes based on the understanding that “what does not get measured, does not get done.”

Training officers at the frontline

Comprehensive and ongoing training for officers, focusing on both cultural competence and practical communication strategies, is also crucial for ensuring that language barriers do not hinder victims' access to justice. Specifically, training on working with interpreters and on communicating with low-proficiency English speakers must be mandatory for all new officers.

Looking ahead

Ensuring that language needs are addressed is not merely desirable, but it is a legal obligation and fundamental to maintaining public confidence in our justice system and the rule of law. Our experience underscores the need for ongoing collaboration between police, access to justice organisations, and the communities they serve. We believe that through improved language needs assessment, enhanced data collection and publication, and relevant training for officers, we can ensure equal treatment for all victims of crime, regardless of language proficiency.

Tips on running an FOI Project

Our FOI journey revealed valuable lessons. Drafting effective FOI questions is an iterative process; initial requests may not yield all the needed data, or any at all. Organisations should be prepared to run requests more than once, refining questions to reduce the time it takes the public authority to complete the task. It is crucial to ask not only about existing or published data, but also about information that may be held in unpublished formats or across different records systems.

Challenges and opportunities of FOI work

FOI requests, especially of multiple bodies, can be time-intensive, and respondents may not always have immediate access to the right data. Building relationships with knowledgeable contacts within police forces or statutory oversight bodies (such as Police and Crime Commissioners) can streamline the process. We have benefited greatly from the kind support of our pro bono partners, A&O Shearman, in providing practical know-how and expanding our capacity, and would recommend such collaborations where possible.

Next steps

We encourage organisations to use this FOI exercise as a template for enquiries, to revisit it in regular intervals (of 2–5 years), and similarly share their findings on this topic.

Further reading

"To be Understood" – victims of crime report October 2024

Language support for victims of crime: “a big mountain to climb” | Clinks

For media enquiries, please contact media@lawcentres.org.uk

Latest News

Monday, 23rd February 2026

Looking back and looking forwardMonday, 16th February 2026

Law Centres Network Intervenes in Mazur Appeal to Address Access to Justice ImplicationsMonday, 26th January 2026

Founder of the Law Centres movement celebrated for major contribution to UK legal profession

Stay in the loop

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to stay in the loop